Auschwitz – Birkenau

Jan 27, 2020, Updated Sep 23, 2021

This post contains affiliate links. Please read our disclosure policy.

On the 75th Anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, we are re-posting this piece in commemoration.

This post contains extremely sensitive topics, which I have tried my best to present to report as I experienced them.

There is some graphic information, and should be skipped if you are sensitive to such topics.

This was my least favorite travel post to write ever – but I feel it is important.

If you are interested in visiting Auschwitz, I have some travel tips at the bottom of my post.

Sweet C’s has chosen to remove all advertising from this post. We strongly believe in the power of understanding history so that we don’t repeat horrors of the past, and want to remove any commercial interest from this post in doing so.

“Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?” — Adolph Hitler

As I was leaving the Armenian Genocide Memorial Museum a few years ago in Yerevan, Armenia, that quote knocked me back in my tracks a bit – but I never really understood just how much it would mean to me until I stepped into the Auschwitz concentration camp.

It was one quote I had never heard – despite studying World War Two (and the events preceding WWII) often – and had never pondered.

For such a simple line, it packs so much history both ahead of it and behind it – the acknowledgement of the genocide of the Armenian people, the fact that the entire world was deaf to their pleas (in fact, most people even today don’t know anything about the Young Turks, the Armenian Diaspora, or the Genocide and still-ongoing political controversy surrounding it- I didn’t until I worked in the United States Senate and a popular band came to our office lobbying for the United States to officially recognize the genocide – something that only a few countries around the globe have done and is quite unlikely America ever will.)

It also can be read to predict the most horrifying and well known genocide in recent history – as packed in that one line were all of Hitler’s plans for Poland, for Jews, and for the rest of Europe.

But nobody knew the scale he’d take it to, and how close he was, for a long time, to keeping it a secret.

Not until long after Auschwitz was liberated by the Red Army (who had their own reasons for not widely publicizing the atrocities that they uncovered) did the world truly know what horrors took place.

Hitler watched the systematic destruction of the Armenian identity, of the way Christians were not only brutally executed, but were enslaved, forced to relocate hundreds and thousands of miles away on gruelingly hot marches through Jordan and Syria, how their land was taken and how the entire world stood by with little realization exactly what was even transpiring – and used it as a model for his world view in a quiet, serene, and beautiful countryside in Poland.

Seeing Adolph Hitler’s quote struck me deep to my core in Armenia – but I never really understood what it meant, or real impact it had, until the first few steps I took into Auschwitz.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” –George Santayana

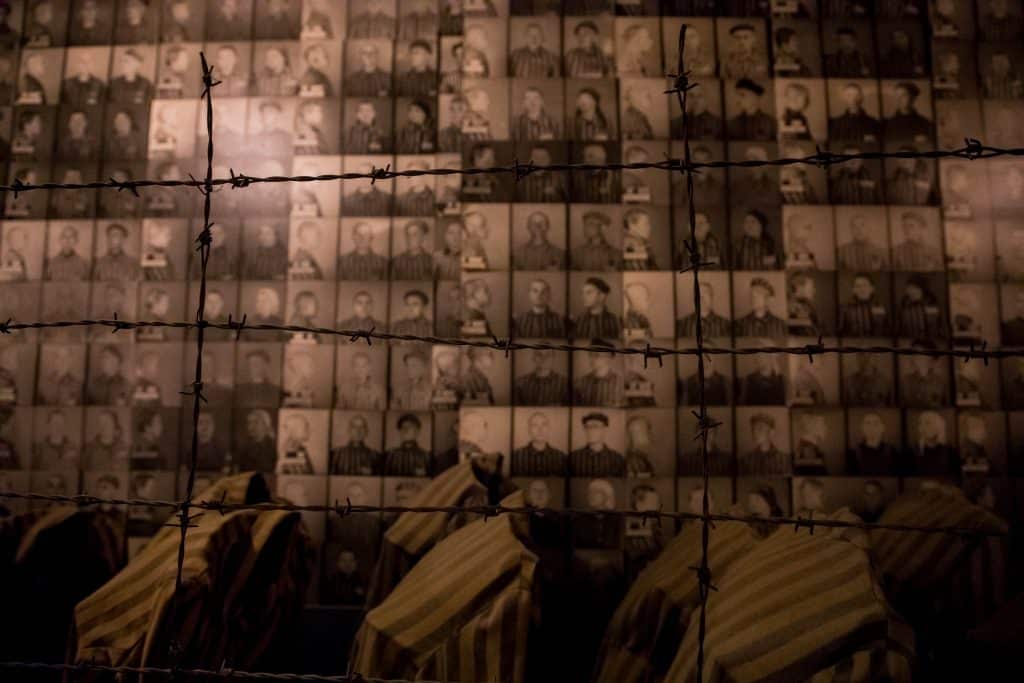

As you enter the extermination exhibit in one of Auschwitz’s blocks, the entire reason this horrible place still stands, invites visitors, and encourages (respectful) photographs and retellings is laid clear – it is our responsibility to never forget the magnitude of the horrors from inside these walls.

It’s unpleasant, and depressing, and macabre, and horrifying – but we can see history already beginning to repeat itself in so many ways even today.

It is our responsibility to understand what happened, so we can examine why it happened and how it happened and we can truly say NEVER AGAIN.

Let me start this post detailing my recent experience visiting Auschwitz by saying that it felt weird, creepy, and even a little gross visiting the camp where hundreds of thousands of people died – let alone taking photos and writing about my experience – but it was encouraged to do so.

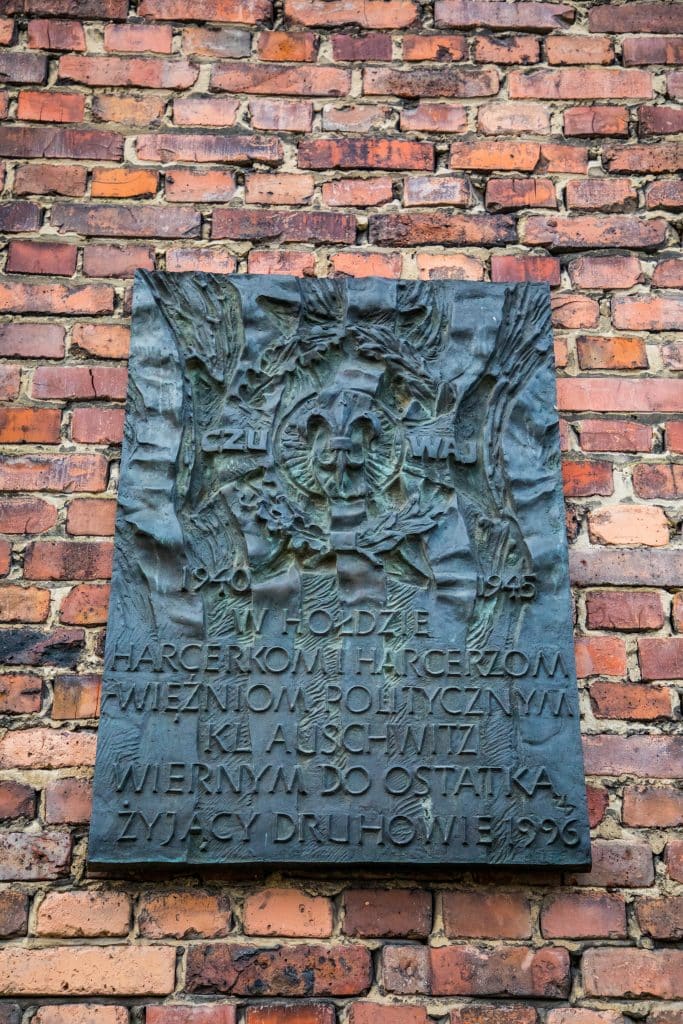

The families of those who died in the Holocaust, as well as descendants of Polish people imprisioned in the lead up to WWII, want to be sure the atrocities are well documented so as never to be forgotten.

Visiting Auschwitz was literally the last thing I wanted to do when visiting Poland – a country I have gone to twice now, which has quickly stolen my heart – but I am forever grateful my friends wanted to go.

I do not care to ever go back, and writing this post was probably one of my least favorite experiences on this website – but I know it is important.

The night I left Auschwitz, I wrote the following on Instagram:

….and after giving myself time to fully absorb the experience, I still feel that way.

This was one of the worst locations I will ever visit (or ever care to), but I do think I am a better person for it – and am challenging myself to not only share what I saw, but to improve what I can in the world going forward.

The air was cold, and small snowflakes circled around on the dreary December day we drove to O?wi?cim from Krakow – and even though we were sort of dreading the destination we programmed into our GPS, we couldn’t help but admire the raw, idyllic beauty Poland’s Silesian region was unfurling for us.

Quiet rolling hills, trees dotting the country side, large, stately homes – it’s an incredibly bucolic drive and on any other sort of occasion, the exact place one might like to spend a long, relaxing vacation in.

After driving through what looks like any other small Polish town, we turned into the Auschwitz I parking lot (Birkenau, the larger and mostly torn down camp, is up the road).

While you can see many of the buildings – and the iconic gate – right there from the road, it doesn’t really hit you until long after you’ve gone through security checks and obtained a ticket (tickets are free- in summer you need to pay a guide for a tour, but in low tourism times like winter you can give yourself a self-tour for free) and walk past the barbed wire lined rail road tracks, under the gate, and start to walk into Auschwitz.

From the road, especially in winter, the whole location looks dreary – but what buildings don’t look a bit dreary in winter?

As you walk closer and through the gate though it hits you – this place is actually quite pretty.

There are perfectly lined rows of frankly adorable brick buildings in great shape- the streets are lined with trees, clinging to the few leaves they refused to shed even though fall has long passed – and the entire place is quiet. If you didn’t know where you were, you might think this was a nice retreat center or apartment complex.

And then you turn, and fully absorb the reality of the place you’re walking into when you read a small sign towards the entrance – as countless Polish officials and prisioners of war, and later gypsies, Catholics, Orthodox, and Jews from around Poland and greater Europe entered this seemingly peaceful place, a band would play to welcome them.

A band.

Playing music to welcome people, to send them out to work, to distract them.

At Auschwitz.

A band welcomed them to the beautiful Polish countryside, to the neatly lined brick homes, to the lines where they’d be sorted – for work, for imprisionment, for medical testing, for torture, for waiting, and for immediate death.

That hid the chambers stocked with Zyklon B, a chemical fertilizer readied to use on humans – that hid the death wall firing line, that hid the tiny cells used to torture prisioners and slowly and painfully kill them in the dark.

That hid the attempted destruction of the Jewish race and the Polish identity- at up to 2,000 souls an hour.

It’s impossible to comprehend the magnitude of suffering – of families being torn apart, of exhaustion, despair, of sadness, hopelessness, and anger – or the feeling of peace that must have washed over people as they first entered Auschwitz, not knowing what those neatly lined buildings held.

That they’d no longer be a human with a name – only a form holding a number.

It’s hard to comprehend people actually bought tickets to the train to Auschwitz (some from as far as Thessaloniki – possibly even some survivors of the Armenian Genocide) thinking this is where they would find peace.

It is even more impossible to comprehend how an entire world had no idea the horrors that took place in those tidy, neat buildings, on tree lined rows of buildings, in a countryside full of lush rolling hills – where an army was able to invade and eviscerate without destroying buildings and infrastructure.

What Hitler learned from the Armenian Genocide was not how to win a war – but how to hide a war. How to create a sense of calm, a working order and exhaust and humiliate your captives.

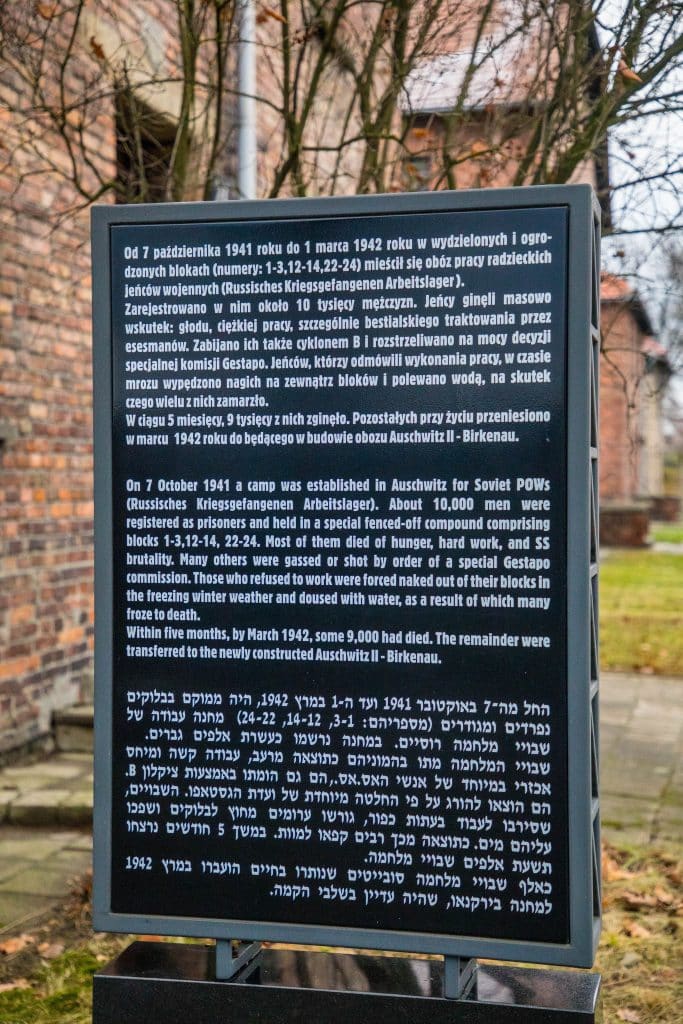

What unspoken horrors and atrocities young Russian soldiers faced as they entered and liberated the camps.

I could not fully comprehend this vital issue until standing in the blocks – Hitler’s plan was successful because the world had no idea what stood inside those blocks.

And while World War II had so much brutal devastation I think that is one of the most horrifying and poignant lessons we must never forget (especially today, as history truly always repeats itself) – a sense of calm, of peace, of a clean exterior appearance concealed the most disgusting things any human can ever think of.

One of the most important reflections I walked away with from the Polish exhibit was the monumental role nationalism played in World War Two (and the build-up of Nazi Germany), and how the Germans exploited the natural human need for organization and identity to maintain order both to encourage their own nation and eliminate others.

When a sense of nationalism is heightened, a country’s people can be blinded to reality and abandon a sense of morality and responsibility to those who do not fit their form – but equally as devastating can be the elimination and destruction of a sense of nationalism, which people rely on to maintain a functional, moral, thriving, and just society.

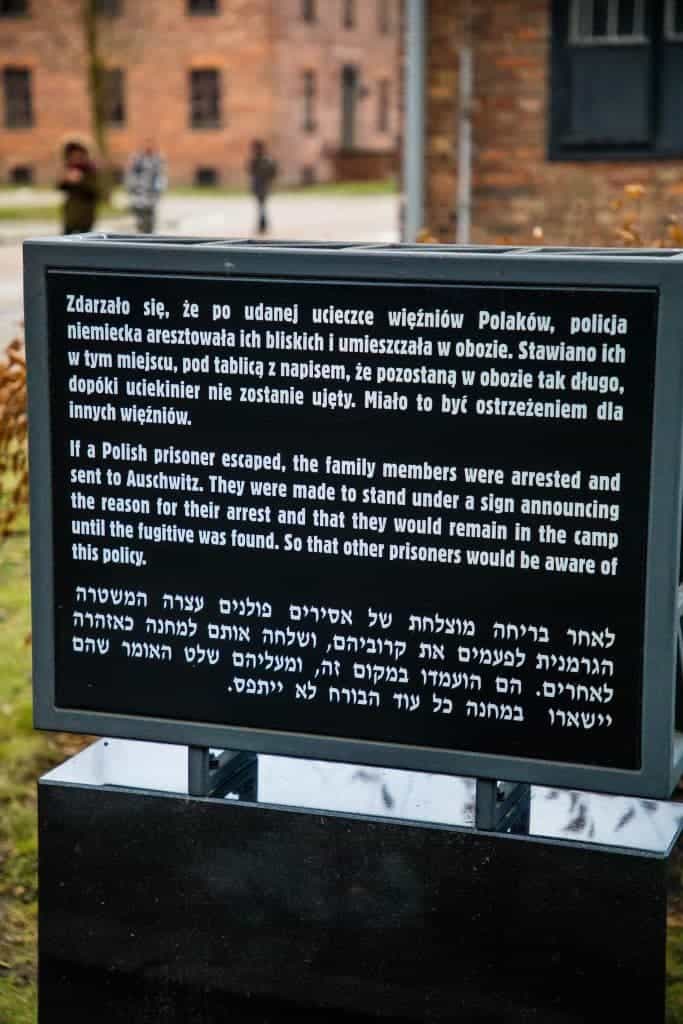

Hitler’s Nazis knew that desiccating the Polish (and then later Jewish) identity would cause the society to collapse – making it easier to target without relying too heavily on ammunition.

By rounding up Polish leaders, politicians, and squashing even their church, it was much easier to quietly and calmly overtake Poland without the rest of the world catching on and coming in to rescue (again, Hitler was certainly inspired by the Young Turks role in the Armenian Genocide).

One of the images that popped into my head, after visiting the exhibit full of hair soldiers cut off the heads of those who had died in the gas chambers was of a woman, sitting at a vanity, brushing her hair.

How this prized possession – an expression of one’s style – was so crudely stripped for a couple dollars trade and made into fabrics.

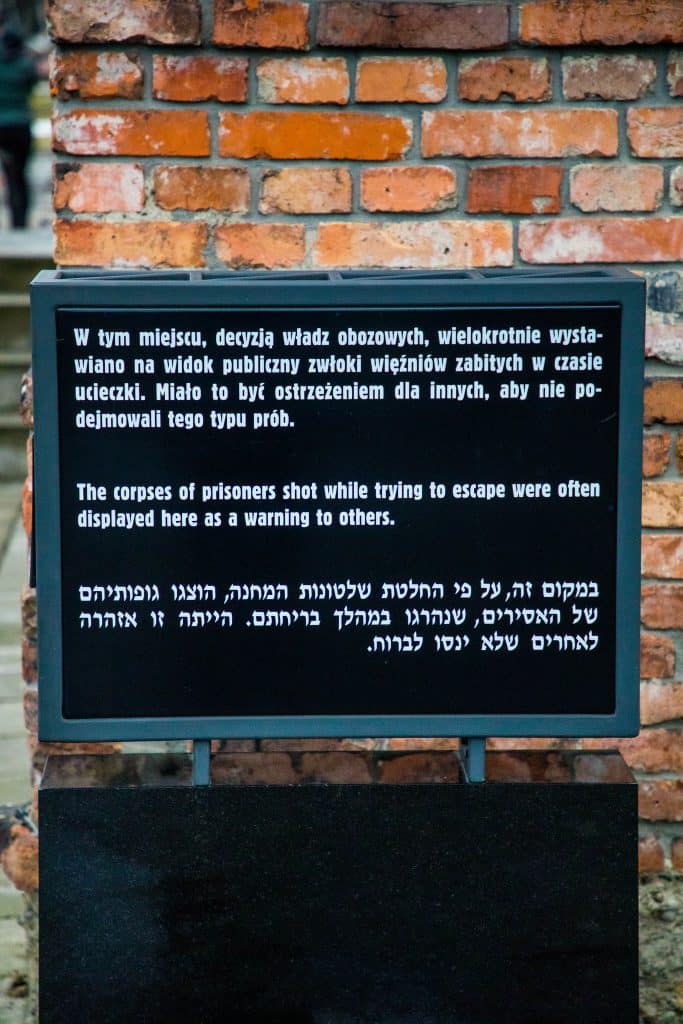

Or the thought of the people, so desperate to escape the chamber through the tiny skylight in the ceiling (not even big enough to slip a hand through, yet big enough to tease a bit of blue sky above) that they dug actual grooves and scratches into concrete walls with nothing but fingers.

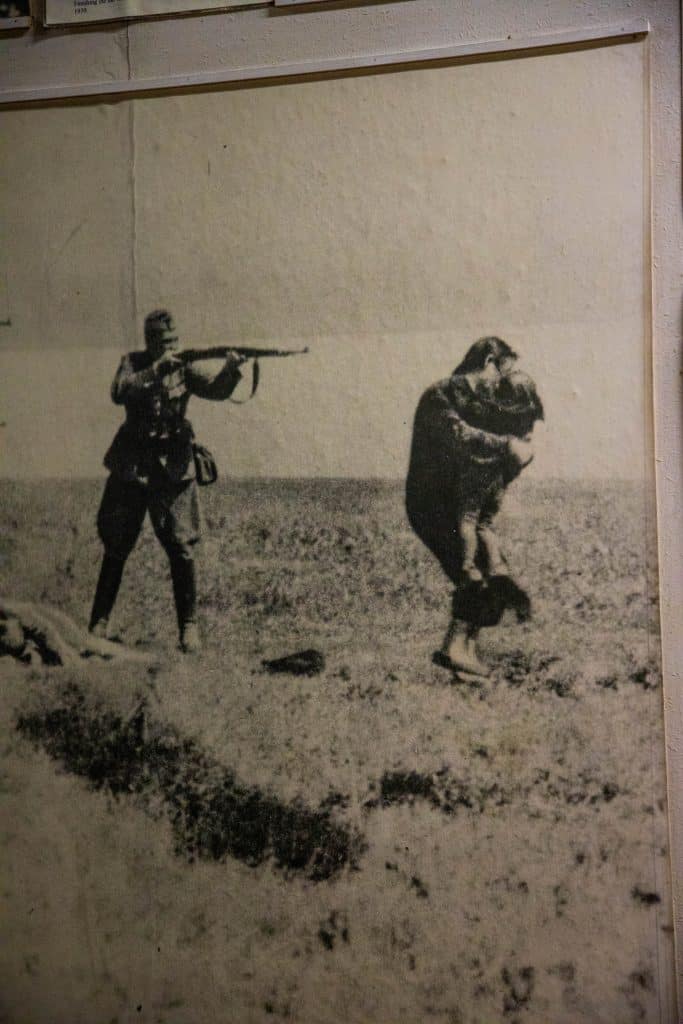

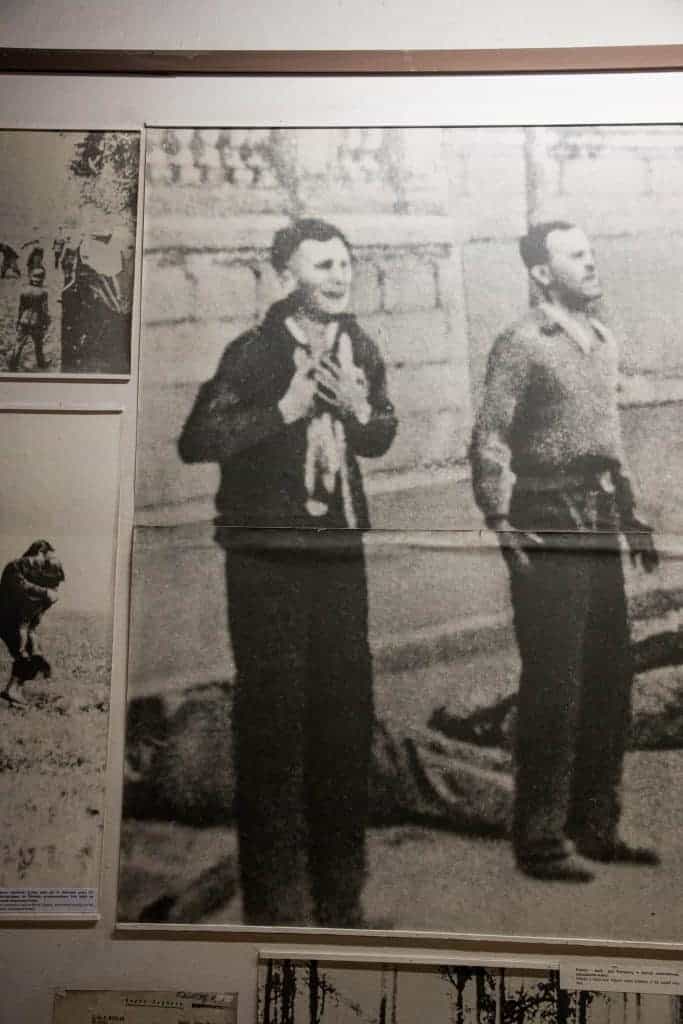

Of the image of a man, standing scared and visibly anguished as he stood against the firing wall, awaiting his fate.

Of the woman, tightly clutching her child in escape through a field, while a soldier readies his gun to shoot her, and her child, as she flees.

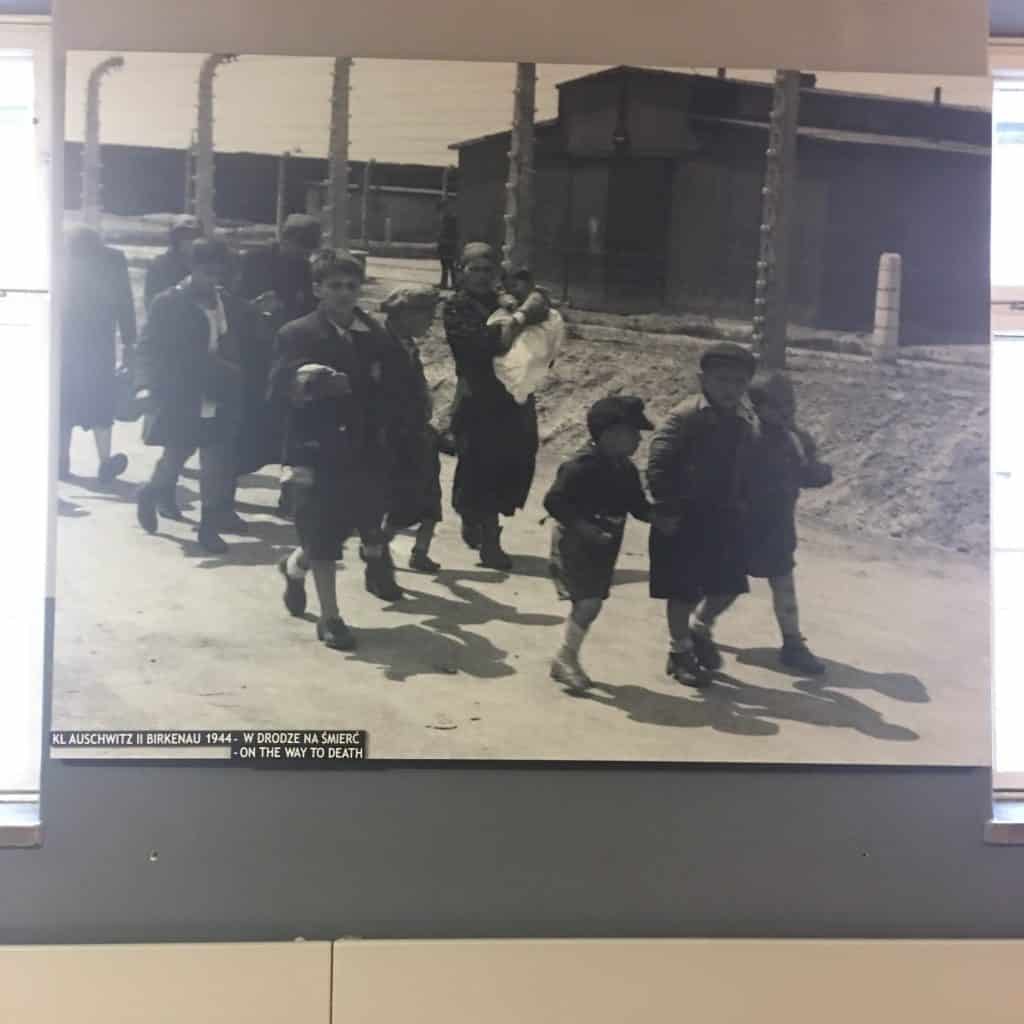

Or the eyes of the children, happily marching, holding the hands of their younger siblings, into a line where they were sent straight to a chamber to never return.

Seeing tons of human hair, teeth, glasses – harvested from the dead – made me physically ill.

The details you never hear about when studying the Holocaust in school were the most horrifying.

Seeing the inside of the gas chamber – feeling the scratches on the concrete wall, and the ovens, outfitted with easy-to-use rails for disposing of victims – was something that will never leave my mind.

I tried so hard to not look at the photographs – it was grueling to do so – but I felt like I had to.

As though if I didn’t look at the images, if I didn’t sear them in my brain (and now tell you all about it), it was for nothing.

If we don’t fully understand the horrors attached to the statement “never again”, how can we truly ensure we stop them from ever happening?

If we don’t honor, remember, and acknowledge the people who perished- even though it is painful and exhausting and depressing to do so – how are we truly preventing this from happening again?

As you walk into building 11, the extermination exhibit,

Silence is exactly what Hitler wanted.

The SS wanted nobody to know what was going on behind those tidy, neat walls.

They wanted the bands to play and to maintain order – even so far as installing shower heads and sometimes issuing soap and towels to people being sent in to gas chambers so as to keep them from panicking.

They delighted in the world’s ignorance to what the buildings held.

They wanted to hide their plans, and had war as the perfect cover.

After all… who, today, speaks of the annihilation of the Armenians.

Tips for travel to Auschwitz:

-If you don’t want to book a tour bus or driver, the drive is very easy. You will take a highway to Oswiecim and it’s a small town to navigate through. Parking is a nominal fee at Auschwitz I, and 7 Zloty at Birkenau (Auschwitz II) next to the Auschwitz Jewish Center.

-Schedule out a day for your visit. Due to our short travel schedule, we visited Auschwitz in the afternoon, before visiting a cheery Christmas market that night. It was an uncomfortable and weird disconnect – it would have been a bit better to have had a quiet night after such an impactful experience. If your schedule allows, give yourself more time to think, reflect, and absorb after visiting.

– If visiting in summer, book a tour guide in advance. Summer months are Poland’s busy tourism season, and a tour guide is mandatory during busy times. You can book a tour online (many groups operate busses or shuttles with a guide from Krakow – both large group, small group, or private tours.)

-If visiting on your own, purchase a book from the bookstore, or download an audio guide. We had a friend who had previously visited, who helped us explore on our own.

-Give yourself a lot of time in each building. Reading all of the signs, absorbing all of the photos, and really experiencing each exhibit (each building has different exhibits built in that range in a variety of topics from the Polish resistance, to medical experimentation, to methods of extermination)

-There are cafes, bookstores, and plenty of information on site. Visiting is made very easy – anything you could need is contained on-site, so you can focus on absorbing everything there.

-Don’t pack a large bag, leave all sharp objects or weapons. This one is self explanatory, but you do go through security gates, bag checks (large bags not allowed) and metal detectors when visiting- much like an airport. Plan accordingly.

-Auschwitz is free to visit, but guides, parking, etc. do have nominal fees and you do need a ticket. If booking through a guide, no need to worry- they will arrange everything you need. If you are showing up in the low tourism season (like we did), you will need to head to the ticket window (past security) and ask for a ticket. They are free, but they will ask you what country you are coming from, and then print out a ticket which is scanned as you go through the entrance turn-styles.

-Consider the closing time. Poland in winter gets dark very early, and admittance is closed an hour before dark. This means the last admittance is 2pm in winter time – so plan accordingly! Find the full operating times here.

-Observe signs and be respectful. Taking photos is encouraged at Auschwitz, but there are exhibits where there are no photographs allowed – both because of the intense personal nature, and to preserve items from the harsh light from flash cameras, as well as to keep sacred spaces quiet from beeps and shutter sounds. There are some exhibits and spaces that respect and silence are requested – as I was reflecting in the chamber, a group of giggling women came in and were loudly talking – which completely irritated me. Remember to be respectful (please, please, don’t take an Auschwitz selfie. Just don’t.) and don’t distract from other people’s experience. Many families of those lost in Auschwitz tour frequently (and some are tour guides) – if you wouldn’t act in a certain way in front of a survivor or family member of someone lost at Auschwitz, don’t do it at all while visiting.

For a full guide to visiting Auschwitz, please read the official Visitor Guide here.

**The following are images that frankly, I didn’t want to post. They completely gutted me and ripped my heart in half.

But for that reason, I think I need to.

Wow Courtney. I am just speechless. You did such a great job with this post and I respect you so much for it.